Gender Gap United Kingdom (UK) - Gender Equality

United Kingdom gender gap draws sharp criticism from advocates as progress remains elusive despite long-standing equality promises.

The United Kingdom has made significant strides toward gender equality in recent decades. However, substantial disparities between men and women persist across multiple domains. This article examines the current state of the gender gap in the UK, analyzing key areas including employment, pay, education, political representation, and health. By comparing UK performance to international benchmarks and tracing historical developments, we can better understand both achievements and remaining challenges.

Gender inequality affects not only individual opportunities and outcomes but also shapes broader economic prosperity and social cohesion. Understanding these gaps therefore matters for policymakers, businesses, and citizens alike. Recent events, including Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic, have created new pressures that sometimes reinforce existing inequalities. Yet they also present opportunities for transformative change.

Economic Participation and Opportunity

Employment Rates and Patterns

Employment rates show substantial improvement in women’s workforce participation. According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), in 2023:

- 72.8% of working-age women were employed, compared to 79.2% of men

- The gender employment gap has narrowed from 13.1 percentage points in 1993 to 6.4 percentage points today

- However, significant gaps remain in working patterns

Women are far more likely to work part-time than men. In fact, 37% of employed women work part-time compared to just 13% of men (ONS, 2023). This pattern reflects continuing gender differences in caring responsibilities and work-life balance expectations.

Moreover, women’s employment experiences differ significantly by:

- Age (with larger gaps for women in their 30s and 40s)

- Ethnicity (with Pakistani and Bangladeshi women having employment rates around 55%)

- Disability status

- Region (with wider gaps in Northern England)

The pandemic disproportionately affected women’s employment. Research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (2022) found that mothers were 1.5 times more likely than fathers to have lost or quit their jobs during lockdowns. Additionally, women were overrepresented in sectors hardest hit by COVID-19 restrictions, such as hospitality and retail.

The Gender Pay Gap

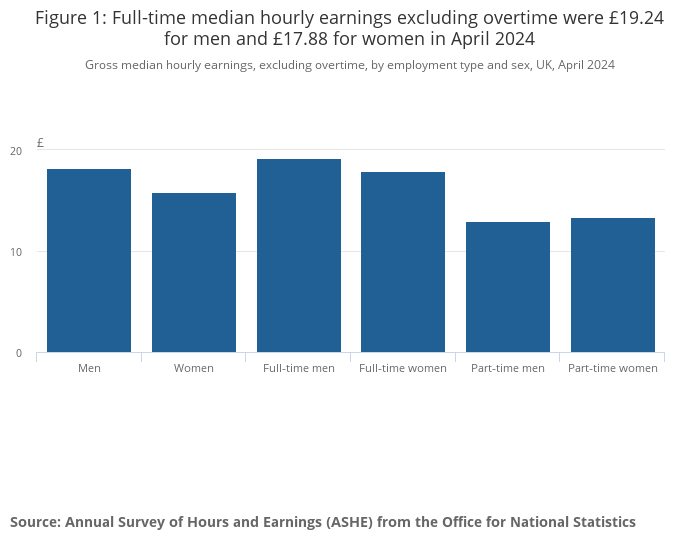

Despite progress, the UK maintains a persistent gender pay gap. According to the latest ONS data:

- The gender pay gap has been declining slowly over time; over the last decade it has fallen by approximately a quarter among full-time employees, and in April 2024, it stood at 7.0%, down from 7.5% in 2023.

- The gender pay gap is larger for employees aged 40 years and over than those aged under 40 years.

- The gender pay gap is larger among high earners than among lower-paid employees.

- In April 2024, the gender pay gap was highest in skilled trades occupations and lowest in the caring, leisure and other service occupations.

- In April 2024, the gender pay gap among full-time employees was higher in every English region than in Wales, Scotland, or Northern Ireland.

- The gender pay gap measures the difference between average hourly earnings excluding overtime of men and women, as a proportion of men’s average hourly earnings excluding overtime; it is a measure across all jobs in the UK, not of the difference in pay between men and women for doing the same job.

Mandatory gender pay gap reporting, introduced in 2017 for organizations with 250+ employees, has increased transparency. However, the Women and Equalities Committee (2022) noted that reporting requirements lack enforcement mechanisms and don’t mandate action plans for improvement.

Occupational Segregation

Occupational segregation remains a key driver of pay disparities. Women concentrate in lower-paid sectors often referred to as the “five Cs” – caring, cashiering, catering, cleaning, and clerical work.

According to the Women’s Budget Group (2023):

- Women comprise 78% of workers in health and social care

- Men make up 89% of workers in construction

- Women represent only 16% of IT professionals

This segregation begins early with educational choices and career guidance. It reflects both societal expectations and structural barriers. Furthermore, traditionally female-dominated sectors typically receive lower pay despite their social importance. For instance, the average childcare worker earns £9.05 per hour compared to £13.12 for the average construction worker (Low Pay Commission, 2023).

Leadership and Career Progression

Women remain underrepresented in senior leadership positions across sectors:

- FTSE 100 companies have only 9.7% female CEOs (up from 5% in 2018)

- Women hold 39.1% of FTSE 100 board positions (Hampton-Alexander Review, 2023)

- Only 27% of UK court judges are women

- In higher education, just 30% of professors are female despite women comprising 57% of total academic staff (Higher Education Statistics Agency, 2023)

The UK has made progress in board representation, but lags behind countries like France (45.3%), Norway (42.3%), and Sweden (39.9%) that have implemented quotas or stronger diversity requirements.

The “broken rung” phenomenon contributes significantly to leadership gaps. For every 100 men promoted to manager, only 86 women receive similar promotions (McKinsey & Company, 2023). This initial disparity compounds at each subsequent career stage.

Entrepreneurship and Access to Capital

Female entrepreneurship represents a significant opportunity for economic growth. However, barriers persist:

- Only 25% of UK businesses are majority-owned by women (Rose Review, 2023)

- Female-led businesses receive just 2% of venture capital investment

- Women are twice as likely as men to cite funding as a barrier to starting a business

The Alison Rose Review of Female Entrepreneurship (2023) estimates that the UK economy could gain £250 billion by supporting female entrepreneurs to the same level as male counterparts.

Political Representation and Power

Parliamentary Representation

Women’s representation in UK politics has improved substantially but remains below parity:

- 35% of MPs elected in 2019 were women (up from just 9.2% in 1992)

- Labour Party has significantly higher female representation (51%) than the Conservative Party (24%)

- The Scottish Parliament (45% women) and Welsh Senedd (43% women) have achieved better gender balance than Westminster

Internationally, the UK ranks 39th globally for women’s parliamentary representation, behind Rwanda (61%), Cuba (53%), and many European neighbors including Sweden (47%) and Spain (44%) (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2023).

Various factors contribute to this underrepresentation:

- Candidate selection processes

- Campaign financing challenges

- Online harassment and abuse targeting female politicians

- Westminster’s working culture and traditions

Ministerial and Cabinet Positions

At the ministerial level:

- Women have held 35% of Cabinet positions since 2019

- The UK has had three female Prime Ministers—Margaret Thatcher, Theresa May, and Liz Truss—more than many comparable democracies

- However, women remain underrepresented in traditionally powerful departments like Treasury and Foreign Affairs

Local Government

Local government shows similar patterns:

- 35% of local councillors are women

- Only 23% of council leaders are female

- Metropolitan areas typically have better representation than rural councils

The Fawcett Society (2023) notes that progress in local government has stalled in recent years, with negligible increases in female representation since 2018.

Work-Life Balance and Care Responsibilities

Parental Leave Policies

The UK’s parental leave system has evolved significantly but remains less generous than many European counterparts:

- Statutory Maternity Leave provides up to 52 weeks, with 39 weeks paid (first 6 weeks at 90% of earnings, remaining 33 weeks at £172.48 per week or 90% of earnings, whichever is lower)

- Paternity Leave offers just 2 weeks at the same statutory rate

- Shared Parental Leave allows couples to split up to 50 weeks of leave

Despite the introduction of Shared Parental Leave in 2015, uptake remains low at 2-8% of eligible fathers (Department for Business and Trade, 2023). This compares unfavorably with countries like Sweden, where 80% of fathers take parental leave.

Childcare Provision and Costs

Childcare represents a significant barrier to gender equality:

- The UK has the third-highest childcare costs among developed nations, with full-time care costing an average of £14,000 annually (OECD, 2023)

- Only 32% of local authorities report sufficient childcare for parents working full-time

- Childcare shortages are particularly acute for disabled children and those in rural areas

The government provides 15-30 hours of free childcare for 3-4 year-olds and some 2-year-olds, with plans to expand this provision. However, funding gaps have led to sustainability challenges for providers.

Time Use and Unpaid Work

Women continue to shoulder disproportionate responsibility for unpaid care and domestic work:

- Women do an average of 26 hours of unpaid work weekly, compared to 16 hours for men

- The pandemic widened this gap, with mothers taking on 65% more additional childcare hours than fathers during lockdowns

- Even among full-time working couples, women perform 60% more housework than men (UK Time Use Survey, 2022)

The economic value of this unpaid work is substantial. The ONS estimates it at £1.24 trillion annually—equivalent to 56% of GDP—with women contributing approximately 64% of this value.

Education and Skills

Educational Attainment

In education, girls and women have reversed historical disadvantages:

- Girls outperform boys at GCSE level, with 73.4% achieving grades 9-4 (A*-C) compared to 64.2% for boys

- Women are 35% more likely to attend university than men

- 57% of UK university graduates are female (UCAS, 2023)

However, significant subject segregation persists:

- Women comprise only 26% of STEM graduates

- Men represent just 12% of nursing and midwifery students

- Computing degrees remain 82% male

This educational segregation directly feeds occupational segregation later in careers. While the UK has invested in initiatives to encourage girls in STEM subjects, progress remains slow.

Educational Outcomes for Different Groups

Gender interacts with other characteristics to shape educational experiences:

- White working-class boys have the lowest university participation rates of any demographic group

- Black Caribbean boys face disproportionately high exclusion rates

- Girls with special educational needs often receive later diagnosis and less support than boys

These intersectional disparities highlight the complexity of addressing gender gaps in education.

Health and Wellbeing

Healthcare Access and Outcomes

The UK healthcare system shows mixed outcomes regarding gender equality:

- Women live longer on average (83.1 years vs. 79.4 for men) but spend more years in poor health

- Women report 30% more GP consultations yet face longer waits for specialist referrals

- Research by the British Medical Association (2023) found that 56% of women feel their healthcare concerns are not taken as seriously as men’s

Particular concerns exist around women’s health issues:

- Endometriosis patients wait an average of 8 years for diagnosis

- Maternal mortality rates are significantly higher for Black and Asian women

- Mental health services fail to address gender-specific needs adequately

The government’s Women’s Health Strategy (2022) aims to address these disparities through targeted funding and policy reforms.

Medical Research and Representation

Healthcare research and delivery show persistent gender biases:

- Women comprise just 25% of participants in cardiovascular clinical trials despite heart disease being a leading cause of female mortality

- Only 4% of healthcare research funding targets women-specific conditions outside of reproductive health

- Female-dominated health professions (nursing, midwifery) receive less research investment than male-dominated specialties (surgery, cardiology)

Violence Against Women and Girls

Prevalence and Reporting

Gender-based violence remains widespread in the UK:

- 1 in 4 women experiences domestic abuse in her lifetime

- Rape convictions reached historic lows in 2022, with just 1.6% of reported cases resulting in charges

- 97% of women aged 18-24 report experiencing sexual harassment in public spaces (UN Women UK, 2021)

The pandemic exacerbated these issues, with domestic abuse calls increasing by 65% during lockdowns.

Policy Responses

Recent policy initiatives include:

- The Domestic Abuse Act 2021, which expanded legal protections and support services

- Increased funding for rape crisis centers and specialist support services

- The Online Safety Bill, which includes provisions to address digital harassment

However, critics note that funding has not kept pace with demand. Women’s Aid (2023) reports that 57% of women were turned away from refuges due to lack of space in the past year.

Intersectional Considerations

Race and Ethnicity

Gender inequality varies significantly by racial and ethnic background:

- Pakistani and Bangladeshi women face an employment gap of 35 percentage points compared to white British women

- Black women are 4 times more likely to die in childbirth than white women

- The ethnicity pay gap compounds the gender pay gap, with Black, Asian and minority ethnic women experiencing a 28% pay gap compared to white British men (Fawcett Society, 2023)

Policy interventions often fail to address these intersecting disadvantages adequately.

Disability

Disabled women face particular barriers:

- Only 53% of disabled women are employed, compared to 65% of disabled men and 80% of non-disabled women

- Disabled women are twice as likely to experience domestic abuse

- Disabled women report facing “dual discrimination” in healthcare settings

LGBTQ+ Considerations

Gender equality issues affect LGBTQ+ individuals distinctively:

- Transgender women report significant barriers to healthcare and employment

- Lesbian women face a smaller pay gap compared to heterosexual women but higher rates of harassment

- Non-binary individuals lack recognition in many formal data collection systems

Historical Context and Progress

Historical Milestones

The UK’s journey toward gender equality includes several key milestones:

- 1918: Some women gained the right to vote (extended to all women over 21 in 1928)

- 1970: Equal Pay Act prohibited differential pay based on gender

- 1975: Sex Discrimination Act outlawed discrimination in employment and services

- 1983: Equal pay for work of equal value established in law

- 2010: Equality Act consolidated and strengthened previous legislation

- 2017: Mandatory gender pay gap reporting introduced

These legal changes reflect broader social movements and shifting cultural attitudes. They represent significant progress from an era when women couldn’t vote, own property independently, or access many professions.

International Comparisons Over Time

The UK’s progress on gender equality can be measured through international indices:

- The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index 2023 ranks the UK 15th out of 146 countries with a score of 0.772 (where 1.0 represents perfect equality)

- This represents an improvement from 26th place in 2006 but a decline from 9th place in 2018

- The UK scores well on educational attainment (1st) but lags on economic participation (38th) and political empowerment (25th)

By comparison, top-performing countries like Iceland (0.91), Finland (0.86), and Norway (0.85) have implemented more comprehensive gender equality policies, particularly around parental leave, childcare, and boardroom representation.

Economic Costs of Gender Inequality

Gender inequality imposes substantial economic costs:

- McKinsey estimates the UK could add £150 billion to GDP by 2030 by fully closing gender gaps in work

- The gender pension gap (40%) results in significantly higher poverty rates among elderly women

- Domestic violence costs the UK economy an estimated £66 billion annually in lost productivity, healthcare, and criminal justice expenses (Home Office, 2023)

These calculations demonstrate that gender equality is not merely a social justice issue but an economic imperative.

Policy Landscape and Initiatives

Current Policy Framework

The UK policy landscape includes:

- The Equality Act 2010, which prohibits discrimination based on protected characteristics including sex

- Gender pay gap reporting requirements for larger employers

- The Public Sector Equality Duty, requiring public bodies to consider equality impacts

- Sector-specific initiatives like the Women in Finance Charter

Post-Brexit, the UK has developed independent equality strategies no longer tied to EU frameworks. The government’s “Build Back Better” agenda includes commitments to women’s economic empowerment, though implementation remains inconsistent.

Corporate and Voluntary Initiatives

Beyond government policy, notable initiatives include:

- The 30% Club, which advocates for greater female representation on boards

- Investor activism through groups like Legal & General, which votes against companies with poor gender diversity

- Sector-specific programs like WISE (Women in Science and Engineering)

- Workplace certification programs like the Gender Equality Certification

These voluntary approaches complement regulatory frameworks but show variable effectiveness.

Media Representation and Cultural Factors

Media Portrayal

Media representation both reflects and reinforces gender norms:

- Women constitute only 28% of expert sources quoted in UK news media

- Female politicians receive disproportionate coverage of their appearance and family lives

- Media depicts a narrow range of acceptable body types and appearances for women

The Creative Diversity Network’s “Diamond” monitoring reports a gradual improvement in on-screen representation but continuing disparities in senior production roles.

Cultural Attitudes

Social attitudes toward gender equality show complex patterns:

- 86% of Britons support gender equality in principle

- However, only 67% identify as feminists

- Attitudes toward motherhood and work remain conservative, with 23% believing mothers of young children should not work full-time (British Social Attitudes Survey, 2022)

These cultural factors significantly influence policy effectiveness and individual choices.

Looking Forward

The UK stands at a critical juncture regarding gender equality. Substantial progress has occurred, yet persistent gaps remain. Several key challenges and opportunities will shape future developments:

Key Challenges

Economic recovery and restructuring: Post-pandemic recovery and labor market changes risk exacerbating gender inequalities without intentional intervention. The growth of automation threatens female-dominated occupations particularly.

Care infrastructure: The UK’s aging population increases care demands, which disproportionately fall on women. Without robust public investment in care systems, progress toward gender equality may stall.

Intersectional disadvantage: Effective policy must address how gender interacts with other characteristics like race, disability, and socioeconomic status to create distinct patterns of disadvantage.

Backlash and resistance: Progress on gender equality has provoked backlash in some quarters, threatening to undermine gains and creating new barriers to advancement.

Promising Approaches

Targeted education and training: Addressing occupational segregation requires interventions beginning in early education and continuing through career development. Particular focus is needed on supporting women in STEM fields and men in caring professions.

Childcare investment: Expanding affordable, high-quality childcare represents one of the most effective strategies for supporting women’s employment and reducing gendered care burdens.

Quotas and targets: Countries with the most significant progress have often implemented mandatory representation requirements for political parties and corporate boards. The UK could strengthen its voluntary approaches with more robust requirements.

Pay transparency: Enhancing pay reporting requirements to include action plans and intersectional analysis would strengthen their impact on reducing pay disparities.

Men’s engagement: Achieving gender equality requires engaging men as allies and addressing masculine norms that constrain both women and men. Particular focus on equalizing care responsibilities would benefit all genders.

Emerging Opportunities

Flexible work normalization: The pandemic-driven shift toward remote and flexible working could support greater gender equality if implemented thoughtfully.

Digital economy: Growth in digital sectors presents opportunities to address occupational segregation through reskilling initiatives and new career paths.

ESG investment: Growing investor focus on Environmental, Social, and Governance factors creates market pressure for gender equality in corporate settings.

The gender gap in the United Kingdom presents a complex picture of progress and persistent challenges. Legal equality has largely been achieved, yet substantive equality remains elusive. Economic disparities, political underrepresentation, and unequal care responsibilities continue to shape women’s experiences and opportunities.

The UK’s international position—performing better than many countries, but lagging behind leaders like Nordic nations—suggests both achievement and unrealized potential. Future progress will require comprehensive approaches addressing structural barriers, cultural attitudes, and policy frameworks.

Gender equality represents not only a matter of justice but also an economic and social imperative. Realizing the full potential of all citizens benefits everyone through enhanced prosperity, improved wellbeing, and stronger communities. The coming decades will determine whether the UK builds on its progress or allows momentum toward equality to stall.

References

British Medical Association. (2023). Gender bias in healthcare. bma.org.uk

British Social Attitudes Survey. (2022). Gender Roles. National Centre for Social Research. bsa.natcen.ac.uk

Department for Business and Trade. (2023). Shared Parental Leave evaluation. gov.uk/government/publications

Eurostat. (2022). Gender pay gap statistics. ec.europa.eu/eurostat

Fawcett Society. (2023). Sex and Power Index. fawcettsociety.org.uk

Hampton-Alexander Review. (2023). FTSE Women Leaders Review. gov.uk/government/publications

Higher Education Statistics Agency. (2023). Staff in Higher Education. hesa.ac.uk

Home Office. (2023). The economic and social costs of domestic abuse. gov.uk/government/publications

Institute for Fiscal Studies. (2022). Gender differences during the COVID-19 pandemic. ifs.org.uk

Inter-Parliamentary Union. (2023). Women in national parliaments. ipu.org

Low Pay Commission. (2023). National Minimum Wage Report. gov.uk/government/organisations/low-pay-commission

McKinsey & Company. (2023). Women in the Workplace: UK. mckinsey.com

OECD. (2023). OECD Family Database. oecd.org/els/family/database.htm

Office for National Statistics. (2023). Gender pay gap in the UK. ons.gov.uk

Rose Review. (2023). Progress Report on Female Entrepreneurship. gov.uk/government/publications

UCAS. (2023). End of Cycle Report. ucas.com

UK Time Use Survey. (2022). Office for National Statistics. ons.gov.uk

UN Women UK. (2021). Prevalence and reporting of sexual harassment in UK public spaces. unwomenuk.org

Women and Equalities Committee. (2022). Gender Pay Gap Reporting: Making it Work. committees.parliament.uk

Women’s Aid. (2023). Annual Survey. womensaid.org.uk

Women’s Budget Group. (2023). Gender and the UK Labour Market. wbg.org.uk

World Economic Forum. (2023). Global Gender Gap Report 2023. weforum.org

World Economic Forum

Global Gender Gap Report UK

The Global Gender Gap Report benchmarks countries on their progress towards gender parity across four thematic dimensions: Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment.

2024

Rank: 14 (out of 146 countries)

Score: 0.789

› report

2023

Rank: 15 (out of 146 countries)

Score: 0.792

2021

Rank: 23 (out of 156 countries)

Score: 0.775

2020

Rank: 21 (out of 153 countries)

Score: 0.767

2018

Rank: 15 (out of 149 countries)

Score: 0,774

2017

Rank: 15 (out of 144 countries)

Score: 0.770

2016

Rank: 20 (out of 144 countries)

Score: 0.752

UN Women UK

Women Count Data Hub: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

Globally, some progress on women’s rights has been achieved. In the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 83.3% of legal frameworks that promote, enforce and monitor gender equality under the SDG indicator, with a focus on violence against women, are in place. 0.1% of women aged 20–24 years old who were married or in a union before age 18. The adolescent birth rate is 11.9 per 1,000 women aged 15–19 as of 2018, down from 12.4 per 1,000 in 2017. As of February 2021, 33.9% of seats in parliament were held by women. In 2012, 86.5% of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) had their need for family planning satisfied with modern methods.

Country Fact Sheet

> data.unwomen.org/country/united-kingdom-of-great-britain-and-northern-ireland